It may seem strange to be writing a review of a book published over 30 years ago – but its subject is Miles Davis, one of the musical giants of the last half of the 20th century and reading it is as challenging as his music was. Moreover, despite being ghosted, it seems that all Quincy Troupe did was write down (with little apparent editing) what Miles said. So, there is little likelihood that Miles would feel mis represented…… which is telling.

My good friend Dave handed the book over to me with the underwhelming recommendation ‘I couldn’t get on with it, there’s only so much use of the term motherfuckers I can take per page. I don’t think he was a very nice man. See how you get on with it!’

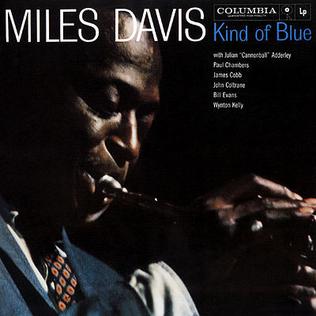

Some context is necessary here. Dave is a hi fi enthusiast with a system that has become steadily more sophisticated and impressive over the 30 years or so that we have been friends. Whenever he has effected an upgrade it has been customary to use a couple of vinyls to ‘test it out.’ These are 1) Solid Air – John Martyn and 2) Kind of Blue – Miles Davis. We both really rate these albums and for me the ‘desert island disc criteria of if you could only take one record’ would, without hesitation, point to the latter. It is generally viewed as one of the best all time jazz albums and the best-selling – so I am not alone in my regard for it.

So, despite not having listened to the majority of his prodigious recording output over 50 years, I see Miles as a colossus – and important to me as a musician. Immediately the reader will identify potential jeopardy looming on the horizon …… and he or she would be right!

Let’s get the review basics out of the way first. The book is very poorly written and I would not recommend it. It does seem that the method employed was for Miles to reminisce, often repeating himself, often introducing a topic with a lazy ‘another thing that happened in 19XX was ………,’ and, as Dave noted, it is over full of expletives and bad mouthing. At just over 400 pages I think a bit more discipline (well a lot more actually) on the part of Quincy Troupe would have made the thing more readable and avoided such a complete trashing of Miles’ personal reputation. I suspect however, that Miles’ arrogance would have not brooked much in the way of changes to the structure or content.

Despite this and Dave’s entirely justified reservations I couldn’t stop reading the thing.

The self-trashing of his personal reputation is almost entirely grounded in his attitude and behaviour towards women. Let’s be clear, these were absolutely atrocious and impacted on a large number of individual women as friends, lovers and wives. He callously used many women for support (including the financing his two lengthy periods of addiction: the first to heroin, the second to cocaine) and physically assaulted others whom he was in relationships with. He routinely justifies his behaviour by blaming the attitudes and behaviours of the women themselves and when he (rarely) acknowledges his own culpability, he brushes it away by saying that is just the way he is. There is no acknowledgement of or sense of any motivation for the need for him to change – it is just how it is.

Miles’ arrogance was no secret. For many years he refused to engage verbally with audiences – refusing to introduce pieces or even band members on stage, with the rationale that his music was what people came to listen to – not to him talking. But it is here that I began to get a glimpse of what had helped to produce such a difficult, unlikable man – the impact of racism. Miles makes a number of references to the stage presence of Louis Armstrong, who he makes clear he rated as a musician, but who he felt had to ingratiate himself with white audiences through his ‘continual grinning’. Miles is adamant that he was not going to follow this path.

His articulation of the impact of racism on Black musicians and Black music as they and it sought to negotiate with the white music industry is one of the strong themes of the book – and of Miles’ life. In the 1940s 50s and 60s in the USA Black musicians were routinely ripped off, had their music appropriated by white musicians and were treated as second class artists. Maintaining control over the rights to their music and making a reasonable living became a constant battle and, according to Miles, a key factor in the high rate of heroin addiction amongst Black jazz musicians. Having to play three sets a night, night after night to small audiences in order to make a living requires a mental and physical stamina that often needed a little help. Despite his own comfortable middleclass family background Miles was also subject to a number of racially motivated arrests and periods of imprisonment. ‘Writing’ in the late 1980s he often observes that ‘little has changed.’

The other strong theme in the book, and I guess the reason I carried on reading it, is music.

Miles chronicles the explosion of bebop (small band, fast paced experimental jazz) in the US in the 1940s and 50s, initially as apprentice to Bird (Charlie Parker) and Dizzy (Gillespie) before largely holding their bands together as their heroin use rendered them increasingly unreliable and unpredictable. He played with all the greats of that era; Thelonious Monk, Cannonball Adderley and of course, John Coltrane with whom he moved from traditional chord-based music to the free-er modal structures that ‘Kind of Blue’ epitomises.

The key to Miles as a musician was not only his virtuosity as a trumpet player and his ability as a band leader to put different musicians together to produce particular types and styles of music but his commitment to constant development. ‘To be creative you must be able to change,’ – with the times, other styles of music and developing technology. He was thus able to continue playing (to very large audiences) and successfully recording until shortly before his death in 1991. He moved from bebop, through modal jazz to rock and funk – always gathering high class musicians such as Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Gil Evans and Marcus Miller around him, drawing on their creativity and expertise to produce stunning and always challenging music. He was very clear in the book that for him making music was a cooperative rather than a competitive undertaking – and I like that, I like that a lot!

However, through reading this book I now have knowledge about Miles the man that I can’t unknow, or justify, or simply wish away. It’s not an uncommon dilemma, we all have artists, musicians, sports people whose work we admire but whose personal lives leave a lot to be desired.

For me, despite the associations, Miles’ music is just too good to discard and I will continue to listen to it, particularly ‘Kind of Blue’ (1959), which is the result of a brilliant collaboration between outstanding musicians who were at the top of their game:

Miles Davis – trumpet

John Coltrane – tenor saxophone

Cannonball Adderley – alto saxophone

Bill Evans – piano

Wynton Kelly – piano

Paul Chambers – bass

Jimmy Cobb – drums

I am in no hurry to read biographies of the other band members …….

Philip Roddis

I too have a slight obsession with Miles. Did you know two books (at least) have been written on Kind of Blue alone? One is by Blue Note archivist, Ashley Kahn, the other – which is a great read – by Eric Nisenson.

As with other jazz legends, larger than life stories – like that of Ben Webster, after a dressing down by Ellington for a below par Cotton Club gig, taking a knife to the Duke’s wardrobe to make jigsaw puzzles of some VERY expensive suits! – about Miles abound.

He was a complex dude and, as your pal suggests, not an especially nice one. He’d often put Bill Evans down – “so that’s your considered WHITE opinion is it, Bill?” – but took a lot of flak from the black power lobby for hiring him at all in what, in the face of stiff competition, many see as his greatest line-up: the one you’ve listed.

My info is that Coltrane and Evans didn’t get on but ‘Trane too defended his brilliant bandmate. In black clubs, hostile audiences would ask, “what’s that white cat doing up there?” Trane would answer: “he’s there because that’s where he’s SUPPOSED to be; he’s there because Miles WANTS him there”. This, apparently, would shut the motherfuckers up.

In similar vein – I’m biased of course as a fellow Yorkshireman – Miles would in the following decade dismiss similar criticisms of his employing John McLaughlin (alongside future Weather Reporter, Joe Zawinul). “Find me a black guitarist who can play like John and I’ll hire him!” That too would STM-FU.

Thanks for the write up. On the strength of it, I too will give this one a swerve. My fascination with the man has its limits!

Philip

PS – re your disappointment in Miles the man as opposed to Miles the musician, history abounds with such mismatches. I heard one spiritual guru, himself a big fan of MD, opine that “the creative impulse is absolutely impersonal: it cares not whether it finds outlet through a Christ or a Hitler; only that it does find outlet. I don’t buy the metaphysical way he put it, but do find myself in sympathy with its deeper truth.

In similar vein, it’s now recognised that Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus was great drama but lousy biography. All the same, its core theme – of Salieri declaring war on God for allowing such divine music to enter the world through so potty-mouthed an imbecile as Mozart – carries a greater truth.

Bryan

Hi Phil

It is clear from the book that for Miles the music was everything. He had to have the right band members for whatever project he was working on, regardless of their backgrounds, ethnicity etc. This is must have been a particularly strong driver as he had a very well developed and strong sense of the need to support Black musicians in what he correctly saw as a very inhospitable and discriminatory world.

I found his commitment to cooperation in music heartening as I have heard some off the cuff comments from stages questioning his authorship of many of his seminal pieces. It is clear that he saw the input of the other musicians he was working with as crucial to the creative process – and credits them accordingly. Over time he came to see himself as more of a facilitator than front person.

I have just received a message from a friend in New Zealand who saw Miles live in London – I am envious!

Philip Roddis

After first seeing Miles live, Bob Dylan declared him the epitome of cool.

Re your point that Miles “had to have the right band members for whatever project he was working on”, his legacy would have been assured solely on the basis of the musicians – Adderley, Coltrane, Evans, McLaughlin, Shorter, Zawinul and more – whose careers he advanced.

What a shame he never did get to work with Hendrix or Prince, both of whom he admired.

In my earlier PS I forgot to close the quote from a spiritual guru. There should be closing quote marks after the second occurrence of “outlet”.

Bryan

Miles did have plans to work with Hendrix and Prince. The former’s death scuppered that and Prince did actually send him a demo track for one of Miles’ albums – but then withdrew it when he heard the rough mixes of the other tracks. Prince said he didn’t think his would be a good fit – but I suspect he felt that his contribution wasn’t up to a comparable standard. If I am right that is telling as Prince had an abundance of talent and self confidence – and says masses about the level that Miles was working at.

As for being disappointed in Miles the man, I had been prepared for that given what I already knew about him – but his utter belligerence and refusal to undertake any self criticism took me by surprise.

As for the creative impulse being impersonal, I wonder whether for it to be realised and developed into an exceptional oeuvre often requires such a laser focus that other human attributes such as empathy, kindness and basic good manners fall by the wayside. It is a depressing thought, and not one I’m going to dwell on …… but I’ve known a few (not in Miles’ league obviously) for whom that cap might fit!